During the winter of 2016, le Centquatre in Paris, a space dedicated to experimentation in the arts, sponsored a program devoted to “The Materiality of the Invisible”. A dozen visual artists explored ways in which what is invisible to the human senses can be seen through relationships between humans and their environment, memory, and the intersection between art and archeology.

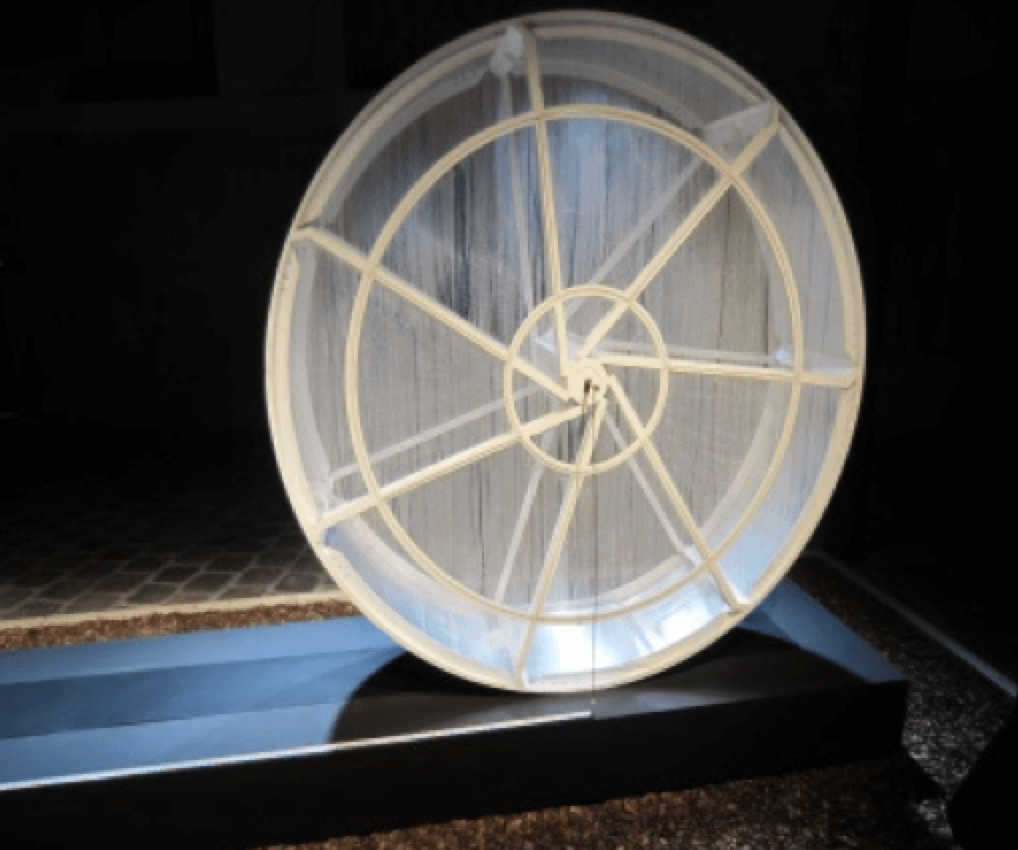

I found “Les Imperciptibles”, three installations by Johann Le Guillerm, particularly mesmerizing. The artist used only natural materials like wood and water to create attractive and precise mechanisms that proved the existence of imperceptible movement. His creations document the power of natural forces to make a difference. By demonstrating the constant movement of changes that are too small and too slow for us to notice, Le Guillerm reminds us that reality reaches far beyond the limits of our perception.

Le Guillerm’s work made me think of other demonstrations of the reality of the invisible. Science centers feature experiments that show the effects of wind transforming still water into crashing waves, electricity raising hair from one’s head, magnetic forces connecting objects across space. While technological discoveries drive us further and further into a mathematically determined reality, we can so easily forget elementary laws of nature, of the universe.

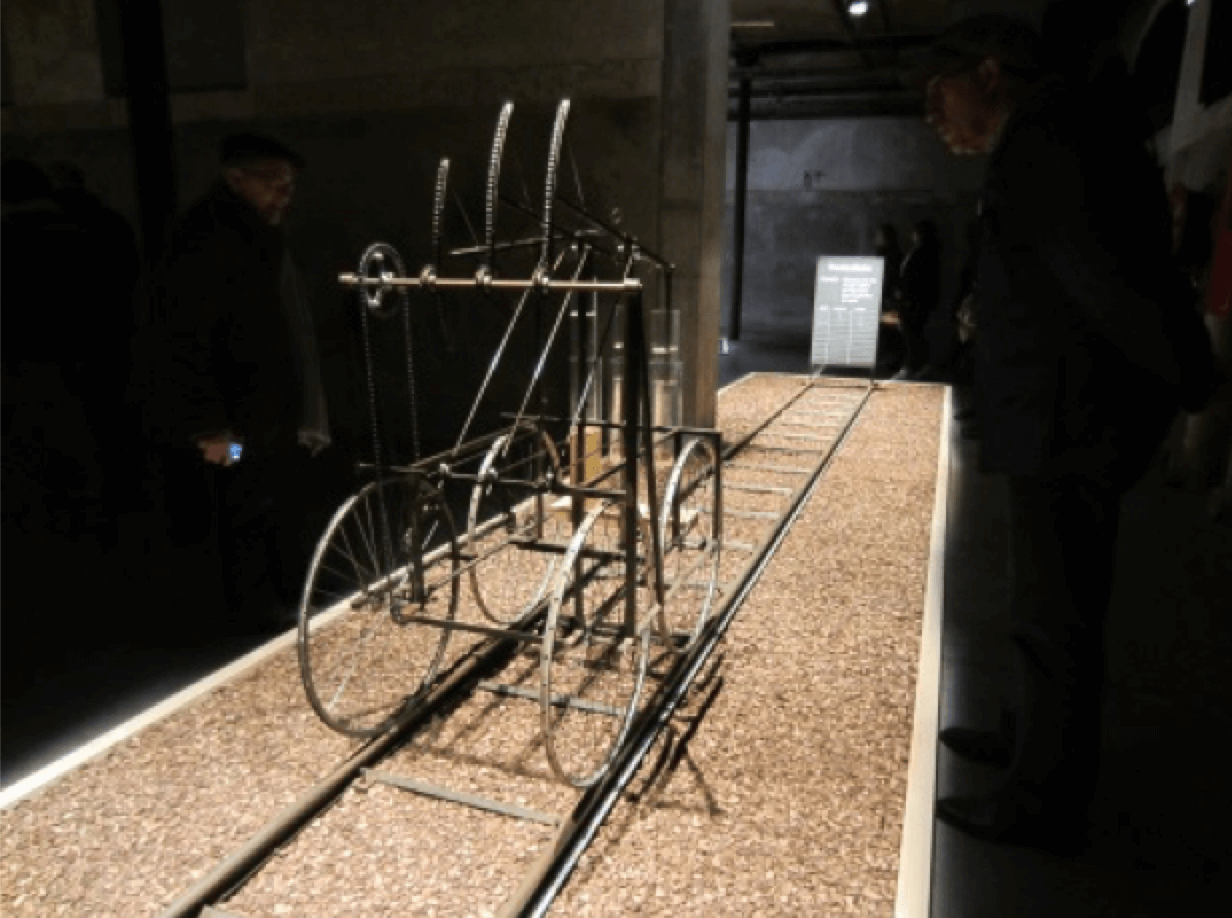

Solitaire, an ingenious installation by Stéphane Thidot at Collège des Bernardins, showed relational realities using wind, wood, water and the visible effects of light to demonstrate change created by movement. Transformation continues without any intervention of the observer, just like our universe continues to evolve independently of our intervention, often in spite of it. The mysterious is everywhere if we slow down long enough to see it. (For a video of the installation, click here – translation not necessary.)

Artists are often the first to explore the ineffable. Although the twentieth century became a time to use art to document the social horrors of our times, to chronicle the brutality and fragmentation that followed two world wars and the harnessing of nuclear energy, it also brought new ways to explore the transcendent, to create beauty.

In a commentary on the history of photography from its mid-19th century origins to our times, Jan Dibbets’ exhibition, “Pandora’s Box”, shows how dramatically the development of the camera has affected our grasp of reality, our understanding of the invisible. From the enormous universe that we can now study through once unimaginable telescope lenses to gazes inside animal and human bodies (or many other forms of matter) made possible with imaging techniques, we have been afforded glimpses into the previously invisible universe. Does the photography make them more real? Not at all – the stars and planets predated our ability to observe them at closer range; the body has evolved from birth to death since people began, regardless of our capacity to identify the changes. And, of course, there is the matter of the heart. All the scans of the world notwithstanding, love is mysterious, and love is real.

Leave A Comment